Why City AI Is About Hosting, Not Owning

- Jan 17

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 26

AI is suddenly everywhere. It powers our phones, our workplaces, our entertainment; and increasingly, our cities. City governments now speak openly about “adopting AI,” positioning themselves as innovators, customers, regulators, and sometimes even competitors in a rapidly expanding AI economy.

But the phrase obscures more than it explains. What does it actually mean for a city to adopt AI?

The answer is rarely straightforward. City AI is not a single technology or policy choice; it is a layered system shaped by governance, infrastructure, capital, and physical constraints. Each city builds on the experiments of the last, adapting AI to its own political realities and material limits. Technology companies tend to welcome this complexity. Cities, by contrast, are less interested in novelty or slogans than in whether a system works and if it can survives procurement, permitting, public scrutiny, and the friction of real-world use.

Miami offers a revealing case.

Rather than attempting to build AI capabilities in-house, the city pursued a public-private partnership model that prioritized hosting over ownership. It focused first on attracting AI compute infrastructure, then layered in familiar economic development tools: a structured host environment, startup competitions, and venture capital incentives designed to encourage companies to build AI applications within the city itself.

In 2025, Miami did something many cities discuss but few execute. It positioned itself not as an inventor of artificial intelligence, but as a platform city, which is essentially a place where AI can be tested, stressed, validated, and commercialized under real-world conditions.

The Brickell AI Digital Twin project, powered by NVIDIA Omniverse and supported by partners including Dell Technologies and World Wide Technology, has often been described as a breakthrough in “city-led AI.” That framing is incomplete. It obscures what is actually novel and consequential about Miami’s approach.

Miami is not building AI models. It is not fabricating chips. It is not designing data centers or training foundational algorithms. What it is doing may be more important: reducing the friction between advanced AI capabilities and the regulated, high-stakes environment of an actual city.

In doing so, Miami is creating application-layer demand that pulls value through the entire AI stack.

That distinction matters. When we fail to see it clearly, public debates blur, accountability weakens, and concerns about cost, power, and beneficiaries miss their mark.

A City as a Host, Not a Lab

The Brickell AI Digital Twin is best understood as a host environment. Miami provides three things that are extraordinarily difficult for private companies to assemble on their own: access, permission, and consequence.

In this case access means real-world data like traffic flows, zoning rules, flood maps, utilities, emergency response systems. This data is continuously updated and politically governed. Permission means regulatory clearance to test technologies that would otherwise stall in endless pilot programs. Consequence means something more elusive but more valuable: when a simulation fails or succeeds, it matters, because it maps to real neighborhoods, real people, and real risk.

The AI itself made up of the compute, GPUs, simulation engines, and predictive models comes from NVIDIA and its ecosystem. Dell supplies the physical stacks. Developers and startups build the applications. Miami does not pretend otherwise, and that honesty is precisely what makes the model work.

Cities that attempt to own AI tend to stall. Cities that invite AI in on structured, negotiated terms become indispensable.

The Digital Twin as a Demand Engine

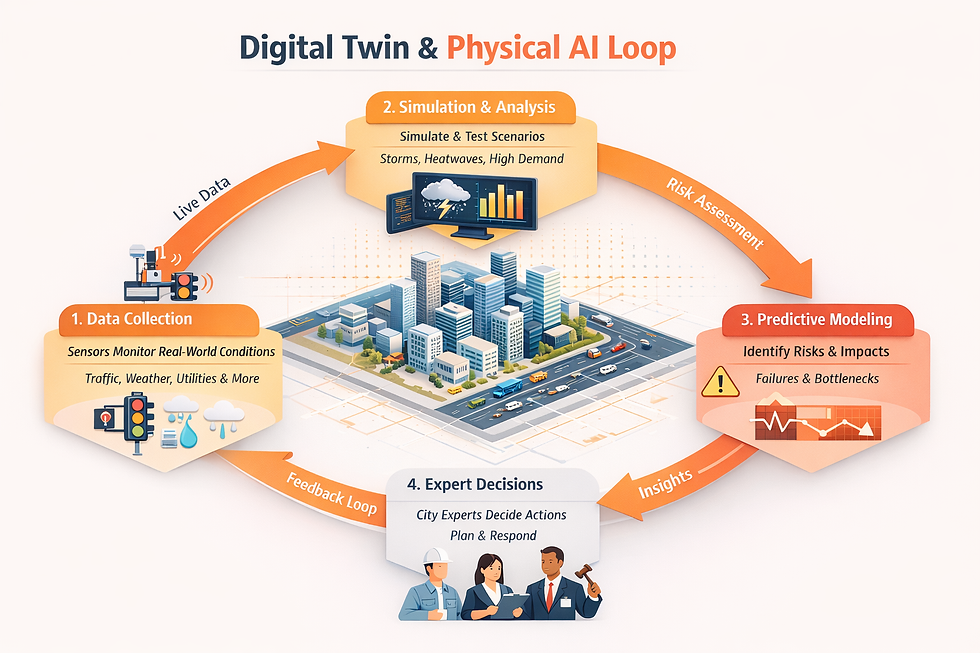

NVIDIA Omniverse enables physically accurate, real-time simulations of the city. But the true innovation here is not visualization; it is persistence.

A city-scale digital twin is never finished. Every new sensor, zoning change, storm pattern, or mobility service triggers re-simulation. Flood modeling alone requires continuous inference as sea levels rise, infrastructure is modified, and weather patterns shift. This is not a one-time compute expense. It is permanent demand.

That demand cascades through the stack:

Application-layer use cases, such as flood resilience, evacuation planning, and mobility testing

Model-layer needs, including computer vision, predictive analytics, and simulation engines

Compute-layer workloads, spanning training, inference, and real-time re-simulation

Physical infrastructure, including data centers, power, cooling, and interconnect

Miami operates at the top of this stack. Companies like NVIDIA, Dell, and infrastructure providers operate below it. The layers are stacked, and rather than compete they compliment.

This is why fears that city AI initiatives will saturate private markets are misplaced. Cities are customers, not substitutes. They cannot internalize this stack even if they wanted to. They lease, outsource, and contract. As host cities, they create durable, politically sticky workloads that infrastructure investors value.

The Cost Question Everyone Misses

One reason the Brickell project unsettles critics is that the city’s direct financial contribution is difficult to isolate. That is not accidental. The public-private partnership structure minimizes visible line items while maximizing participation.

Miami’s primary costs are administrative and infrastructural: coordination, permitting, data access, and selective subsidies. The most expensive components is the AI infrastructure and hardware (the GPUs, compute stacks, and data centers) are absorbed by private partners as part of their cost of goods sold and long-term market strategy.

This is not evasive governance. It is strategic governance.

Had Miami attempted a fully city-funded AI build, the project would likely not exist. By designing itself as a testbed rather than an owner, the city made participation attractive to companies willing to put real capital at risk.

Why the Model Works

Miami understands something many cities overlook: its comparative advantage is not invention. It is relevance.

AI companies need cities more than cities need AI companies. Without real-world deployment, AI remains speculative. Miami is monetizing its relevance by offering itself as a proving ground.

This posture is not passive. It requires political leadership, cross-agency coordination, and a tolerance for experimentation. What mattered was not branding, but the signal of regulatory openness coupled with the institutional capacity to translate that signal into real partnerships, building on earlier work from a smaller digital twin project in Coral Gables that proved the digital model could function beyond theory.

The result is a city that does not invent AI but makes its deployment inevitable.

Miami is not building the future of artificial intelligence. It is building the market conditions that force that future to arrive.

Comments